Bordeaux Basics: Into the World of Classic French Wine

Bordeaux is probably the most studied wine region in the entire world. This is not only because it is a bastion of high-quality classic French wine, but also because it is incredibly complex, bureaucratic and immensely detailed. When delving into this world it can seem insurmountably difficult, with confusing terminology being the first significant hurdle. If you get past this step then you are faced with trying to figure out what is even in the wine. The bottles themselves are unhelpful, with labels often neglecting to inform us of the precise blend of grapes used in each wine (there are very often up to four varieties). Even when you find out this information it could be for nothing, since the next vintage will likely mean a different blend. However, the most important aspect of Bordeaux wine is knowing your Pomerol from your Pauillac or your St. Emillion from your St. Estephe. These famous names in wine are probably the easiest way to get your head around the region, with certain areas having distinct characteristics, grape varieties and styles of wine.

Bordeaux therefore is incredibly complicated. Not only do you have to learn the regions and sub-regions which divide the land, but it is also very helpful to know each and every vineyard and wine producer. However, using some broad brush strokes Bordeaux can be divided into five main areas: Medoc wines from the lower left bank of the estuary; white and dessert wines from Graves and Sauternes further up on the left bank; right bank wines from St Emilion, Pomerol and their satellites; the hilly côtes vineyards of Bourg, Fronsac and Blaye on the same side of the river; and wines of both colours from the Entre-Deux-Mers region between the Garonne and Dordogne.

While even this may seem daunting, I will be delving into further detail about the first four of these areas over the next couple of blogs, focusing on the left bank and the right bank in turn. However to begin this Bordeaux trilogy, this blog will be a general overview of the entire region, along with some exploration about the larger, less specialist area of Entre-Deux-Mers.

A Bordeaux Overview

The central arteries of Bordeaux are the rivers. Like most of the best wine regions in the world Bordeaux revolves around a system of major rivers, in this case the Garonne, the Dordogne, and the Gironde estuary where the two meet. This is no coincidence since a river – or indeed any large body of water – can produce a moderating effect on the local climate, and this can help to create the consistent conditions which are ideal for viticulture.

Additionally, the flow of two great rivers through the landscape inevitably leaves its mark, shifting the ground and its soil around for centuries. This is why some vineyards produce consistently excellent and unique wine while others not too far away can only manage to produce low quality, cheap wine. In fact, there is constant competition between winemakers to get hold of the very best parcels of land with the best soils, to ensure the resulting wine is of the very highest standards. Competition can be fierce since there are over 6,000 wineries in the region, with some 110,000 hectares of land covered in vineyards. Most of this area is devoted to producing classic red wines. In fact, 90% of all wines produced are red and include Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon. Both these grapes originated in the area and are still grown in huge quantities today.

One of the most important things to know about Bordeaux wines is that they are a blend of grape varieties. The red Bordeaux blend is one of the most copied around the world and it includes a variety of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carménère. However, this doesn’t mean Bordeaux doesn’t produce some excellent white wines as well, the only problem is that they are severely underappreciated.

Although, this wasn’t always the case. It is documented that the Romans began planting grapes in the area as early as 43 BCE. At this time the main variety was the white grape Savagnin Blanc (not to be confused with the now common Sauvignon Blanc), as well as some Pinot Noir. Under English control from the 12th to 15th centuries, the region began to become a major exporter of wine for the first time, sending large amounts of wine to England, which quickly began to develop the taste for it. Despite this, following the end of Hundred Years’ War this export market shifted to the emerging commercial powerhouse of the Dutch who established themselves quickly over the following centuries. This involvement became significant in the 1650s when the Dutch, experts in managing low lying swamplands in their own country, began to drain the marshy left bank of the estuary. This transformed this area into a rich vine growing area, now called Medoc, which became the foundation for the large scale production of quality wine for the northern European market.

It took till 1855 for the French government under Napoleon III to first begin classifying Bordeaux wine. This ranged from the five Premiers Cru (first growth) wineries which were intended to be the very best of Bordeaux, down to Cinquièmes Crus (fifth growths). Within each category, the various châteaux are ranked in order of quality and only twice since the 1855 classification has there been a change: first in 1856 when Cantemerle was added as a fifth growth and, more significantly, in 1973, when Château Mouton Rothschild was elevated from a second growth to a first growth vineyard after decades of intense lobbying by the powerful Philippe de Rothschild. This had led to much complaint about a system which has not been changed for almost 170 years. The most significant attempt to reform the system came in 1960, when a newly proposed classification was drawn up, however there was no success. Alexis Lichine, a member of the 1960 revision panel, launched a campaign to implement changes that lasted over thirty years, in the process publishing several editions of his own unofficial classification. In support of his argument, Lichine cited the case of Chateau Lynch-Bages, the Pauillac Fifth Growth that, through good management and by patiently collecting the best parcels as they come on the market, makes wine that are worthy of a much higher classification. Conversely, poor management can result in a significant decline in quality, as the example of Chateau Margaux shows—the wines it made in the 1960s and 1970s are widely regarded as far below what's expected of a First Growth.

Entre-Deux-Mers

The first region that I will introduce you to is probably the illustrious and lacks any form of name recognition that other regions enjoy, mainly due to the lower quality of wine produced here. This region is called Entre-Deux-Mers which translates as ‘between two tides’, referring to its location between the tidal rivers Garonne and Dordogne. While this is the largest of the Bordeaux regions it is one of the least densely planted, with around only half the landed devoted to vineyards, the other half belonging to large forests peppered by small villages.

Entre-Deux-Mers is not one region, but instead has some relatively smaller areas producing slightly different types of wine. The most interesting of these are Premières Côtes de Bordeaux and Cadillac which occupy a thin sliver of land along the Garonne River. Here, sweeter and lighter, wines of both colours can be found with a certain elegance to them.

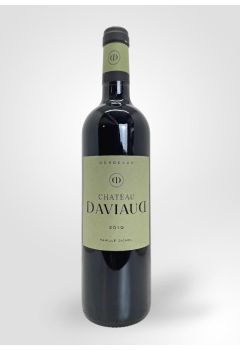

The majority of the area though produces wine with the lowest classification of ‘Bordeaux’ or ‘Bordeaux Superior’. This doesn’t necessarily mean these wines are of worse quality than other more prestigious names, but it does hide both great and poor wines. For example, the Chateau Daviaud we sell at Weavers is a wine of true quality for its price. However, this is most likely due to the producers: ‘Famille Sichel’ who have decades of experience producing masterful wines in Médoc. This relates back to a point I made right at the start of this blog, that region and classification pale in comparison to understanding the skill and processes of each winery. The very best names can hide very average wine, while lowly names can hide some surprising delicious (and cheaper) wine.

Featured

Château Daviaud, Bordeaux, 2019

Deep and rich

What is MIX6?Add 6 or more bottles of selected wine to your basket to receive the wholesale price.