-

- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro Valley

A wine of dark colour, resembling ripe cherries, with aromas of red and black fruit with a hint of florality. In the mouth, it reveals the characteris... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro Valley

A wine of dark colour, resembling ripe cherries, with aromas of red and black fruit with a hint of florality. In the mouth, it reveals the characteris... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

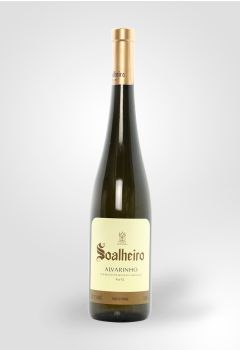

- Vinho Verde

A zesty dry white made from local grape varieties. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

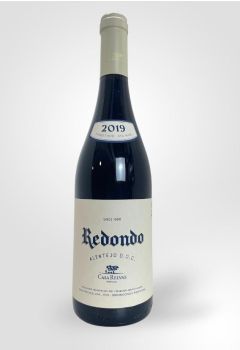

- Alentejo

It's ripe and juicy, has a great mix of warming, dark plummy fruit and crunchy red berries, with a little lift of floral violets. There's earthy, almo... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Alentejo

It's ripe and juicy, has a great mix of warming, dark plummy fruit and crunchy red berries, with a little lift of floral violets. There's earthy, almo... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Bairrada

This lovely Pet Nat sees three days of maceration on the grape skins. This is then followed by a pre-fermentation in plastic vats, and the fermentatio... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Bairrada

This lovely Pet Nat sees three days of maceration on the grape skins. This is then followed by a pre-fermentation in plastic vats, and the fermentatio... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Carcavelos

Clear yellow golden hue. Pronounced nose of orange marmalade with a honeysuckle floral note. The palate has sweet orange & dried stone fruit with ... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Carcavelos

Clear yellow golden hue. Pronounced nose of orange marmalade with a honeysuckle floral note. The palate has sweet orange & dried stone fruit with ... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Alentejo

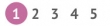

A wine with an intense garnet colour and aromas of black fruit jams, ripe olives, mint and spices. Its structure is distinct, possessing a clear fresh... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Alentejo

A wine with an intense garnet colour and aromas of black fruit jams, ripe olives, mint and spices. Its structure is distinct, possessing a clear fresh... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

Mineral, lemon, lime and flint on the nose. Reductive and fascinating. Medium to full body with creamy texture. Lemon rind and curd. Some nougat and s... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

Mineral, lemon, lime and flint on the nose. Reductive and fascinating. Medium to full body with creamy texture. Lemon rind and curd. Some nougat and s... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Alentejano

Intense aromas of red berries with some spicy notes coming through the ripe fruit flavours. The palate is smooth with soft tannins supporting generous... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Alentejano

Intense aromas of red berries with some spicy notes coming through the ripe fruit flavours. The palate is smooth with soft tannins supporting generous... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

A medium-dry Madeira with good fruit content and a dry finish. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

Well balanced with smooth aromas and a non-cloying sweetness. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro

Rich and fruity, a very good ruby port. Read More -

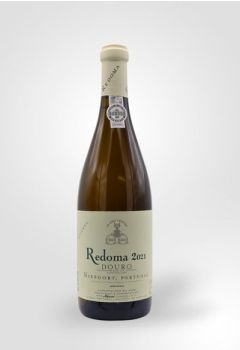

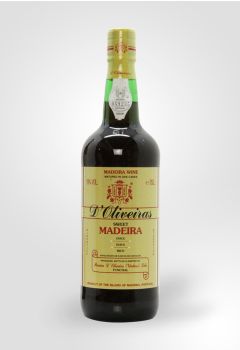

- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro

Immensely fruited with a balanced concentration of flavours. Niepoort Late Bottled Vintage ports just go from strength to strength. Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro

Immensely fruited with a balanced concentration of flavours. Niepoort Late Bottled Vintage ports just go from strength to strength. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

A plethora of aromas detectable on the nose with apple, citrus and tropical fruits leading the way. The palate is elegant and balanced with great stru... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

A plethora of aromas detectable on the nose with apple, citrus and tropical fruits leading the way. The palate is elegant and balanced with great stru... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

Aromas of red fruit, cassis and some floral overtones fill the nose, with a hint of spice. In the mouth, the wine is rich with a medium to full body a... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

Aromas of red fruit, cassis and some floral overtones fill the nose, with a hint of spice. In the mouth, the wine is rich with a medium to full body a... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

A round and soft Port, with lots of sweet berry and plummy fruit, verging on jam. Full bodied and round, with a long, sweet finish. Read More- Origin

- Portugal

A round and soft Port, with lots of sweet berry and plummy fruit, verging on jam. Full bodied and round, with a long, sweet finish. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

Inky black in colour with concentrated blackcurrant and blackberry aromas. There are also notes of coffee and hints of wild herbs and mint. Jammy frui... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

Inky black in colour with concentrated blackcurrant and blackberry aromas. There are also notes of coffee and hints of wild herbs and mint. Jammy frui... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

Deep, rich and luscious with herby cassis fruits. Soft and fruity on the palate with a finish of liquorice and chocolate. A classic Vintage Port. Read More- Origin

- Portugal

Deep, rich and luscious with herby cassis fruits. Soft and fruity on the palate with a finish of liquorice and chocolate. A classic Vintage Port. Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

Almost black in colour with dark cherry fruit, quite like sweet plums, with some wet earth and leafy notes. Quite full bodied with good tannins and a ... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

Almost black in colour with dark cherry fruit, quite like sweet plums, with some wet earth and leafy notes. Quite full bodied with good tannins and a ... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

A strong summer fruit character with abundance of raspberries and strawberries. This is supported by some floral notes and a touch of spice as the mou... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Tejo

A strong summer fruit character with abundance of raspberries and strawberries. This is supported by some floral notes and a touch of spice as the mou... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Peninsula de Setubal

Deep amber in colour, this wine is rich and smooth with a full flavour that has a strong raisin fruit character paired with caramel, citrus orange pee... Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Peninsula de Setubal

Deep amber in colour, this wine is rich and smooth with a full flavour that has a strong raisin fruit character paired with caramel, citrus orange pee... Read More -

- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro

An excellent and complex 10-Year-Old Tawny with aromas of spices followed by elegant notes of honey, wood and dried fruit. Read More- Origin

- Portugal

- Douro

An excellent and complex 10-Year-Old Tawny with aromas of spices followed by elegant notes of honey, wood and dried fruit. Read More

Portugal is notable for resisting the world-wide trend of adopting international grape varieties and, accordingly, indigenous vines are responsible for almost all of its wines. Some of these vines are superb, but rarely have they travelled successfully abroad, and this makes Portugal a unique place to explore.

History

The history of Portuguese winemaking bears many similarities to that of Spain. The Phoenicians, the Greeks and especially the Romans established it here, a mid-20th century dictator damaged it hugely, and only since entry into the EU in 1986 has it revived. It may have been the British, however, who shaped it the most.

When Napoleon threatened the white cliffs of Dover, he inadvertently popularised Port and Madeira in Britain. Port, in particular, was already known at the Georgian table but when Bordeaux and Burgundy became out-of-bounds in the early 19th century demand for it rocketed. The fortification of these wines, so integral to their essence, was an innovation intended to preserve them at sea on their way over to Britain.

The Classification System

Paradoxically, the Portuguese system of classification is both one of the oldest and one of the newest, certainly in Europe. In 1756 the prime minister drew a line around the Douro to protect the quality of Port, but few further strides were taken until entry into the EU in 1986. At this time a system was drawn up in imitation of France's, but which suffered from all the bureaucratic inflexibility of the Italian attempt. Only time will tell whether the system comes to reliably indicate quality.

Climate and Conditions

By a wonderful quirk of nature, Portugal has a varied climate working with a topography that frequently makes anything but vines a nuisance to grow. The Atlantic coast is wet, cool and a land of light reds and whites. Inland is particularly known for its reds, and in the high, hot north they can be powerful and impressive. It is here, in the inaccessible, inhospitable Douro, that the grapes for Port are grown. On the volcanic soils of Madeira, irrigation is necessary except up in the clouds at high altitude.

The Wines of Today

Portugal, with its suite of indigenous grapes, traditional techniques and thirsty inhabitants, and with the exception of Port and Madeira, has always produced wine for itself instead of the world. Yet this is beginning to change, and the good news for the consumer is that the transformation does not involve vast plantings of international vines that have spread elsewhere in the world. Individuality has been preserved, and Portugal is improving and exporting whilst retaining its traditional and inimitable character.