Lies, Redemption and Eiswein – Austrian Wine’s Ascent from the Depths of a Scandal

Austrian wines are all of exceptional quality. It doesn't really matter which one, because they are so fixated on the quality of the wines they export that it is very difficult to find a bad bottle. In fact, Austria focuses almost obsessively on this issue, for one particular reason.

There was a time when the reputation of Austrian wine was burnt to the ground, leaving the industry reeling for two decades. I'm not saying their reputation for wine was great before then; most of the wines produced were sweet and cheap. But a shocking discovery had their bottles taken down from shelves across the world. So what actually happened?

Before 1985 the wines of Austria were similar to those of Germany. They were often sweeter on the Pradikatswein ripeness scale which gives a quality level based on the length of time the grapes spend on the vine and the quality of the grapes. The sweeter the wine the better the quality and the higher the price. These levels are Qualitatswein, Kabinett, Spatlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese. Importantly though, Austrian wine was mass produced and cheap. A lot of it was shipped to Germany to be bottled and sold, where if somebody wanted a Beerenauslese at an affordable price they could get an Austrian one.

In the 1970's many Austrian importers signed lucrative contracts with West German supermarkets and shops. Those contracts dictated the quality level of the wine to be supplied, like Beerenauslese for example. The problem was that the early 1980's saw a climate in Austria that made for difficult growing conditions. The grapes weren’t sweet enough since they couldn't get to the necessary ripeness for those designated quality levels. In particular, 1982 was a terrible year and Austrian winemakers panicked when there wasn't enough quality wine being produced to meet the requirements of their contracts. The wine was thin and sour, nothing like what was expected for the German market. So some people took matters into their own hands and decided to look for ways to improve the poor quality wine being made. Typical sweeteners weren't producing what they wanted, so something else had to be done. The solution was diethylene glycol. It was being used to add body and sweetness to inferior wines, imitating those of higher quality.

West Germany had been the victim of illegal sweeteners before by Italian wines in 1980 and 1982, and with the new technology of 1985 there were laboratories that had begun running tests on bottles of wine for quality control. On June 27th they found a bottle of Austrian 1983 Ruster Auslese in a Stuttgart supermarket that contained diethylene glycol. More bottles from Austria were found with the chemical. Global outrage ensued.

Diethylene glycol, also known as DEG, is a chemical used for antifreeze. It's lethal in large volumes, yet even at lower levels it can still pose a serious threat to health. Most of the bottles that were found only contained a few grams per litre, so you'd die of alcohol poisoning before you die of the DEG in one sitting. But just 0.1 grams per litre is enough to do brain and kidney damage with long-term consumption.

Almost immediately it came out that the Austrian government knew about the tainted wine three months before it was discovered in West Germany. The Austrian Agriculture Minister Günter Haiden claimed that they had informed the courts and authorities in April, and that they instead should be held responsible for not informing the public. After this clear admission of guilt everybody was calling for Hadien to step down.

After initially denying any knowledge, the West German government eventually admitted they had been informed by Austria on May 10th. It wasn't until the scandal had made international news that they pulled every bottle of Austrian wine off the shelves for destruction and further importing was banned. This whole thing was such a big deal that "glycol" was made the 1985 word of the year in West Germany. In Austria, a hotline for the public was made for any questions, advice and possible leads.

At first it was thought that West Germany was the lone destination of the tainted wine, but it was quickly found that the destination didn't matter. At that time around 1,500 brands of Austrian wine were imported into the United States and, rather than destroying all of the bottles like West Germany did, American retailers could keep selling them if it was proven that they contained no DEG. Four bottles were found in the first month. By the end of August, the count of contaminated bottles in the U.S. was 26.

The scramble to cover tracks began. Anton Schmied panicked and dumped 4,000 gallons of his red wine into the town sewer, where the DEG killed the microorganisms that clean the waste. Dead trout started appearing as untreated sewerage emptied out into the streams. Schmied was later arrested. Therefore, evidently the Austrian wine couldn't be destroyed just by emptying barrels and breaking the bottles to have it go down the drain. Instead, it was put to good use. The wine was used as a cooling agent in the ovens of cement plants instead of water. In Germany though, 27 million litres of wine was destroyed by the authorities.

One month into the scandal, 28 people had been arrested including the man that started it all and his son. Otto Nadrasky Sr. He was a chemist and wine consultant from Grafenworth, Lower Austria. It was his idea to use diethylene glycol, and from there it spread in a top secret web of connections. Sentencing of over thirty suspects began as early as October, and the first punishment handed out was a year and a half in prison. Karl Grill, a winemaker and the proprietor of Firma Gebruder Grill, took his own life after his sentencing.

No one was harmed or killed by the contaminated wine, at least that we know of. Which is even more surprising with the discovery of wines that reached up to 48 grams per litre of DEG. But the fact that it cannot be proven is telling of the confusion and lies spreading around the industry. Even with no physical harm done from consumption, sales dropped enormously. Exports of Austrian wine averaged 205 million litres previous to 1985. This dropped dramatically to 20 million litres in 1986. Mayor Heribert Altinger of Rust, an Austrian town that was glycol free but still suffered greatly from the drop in sales and tourism, commented that "It is the worst disaster to hit this region since World War II.

Economist Karl Aiginger said of the lasting impact of the scandal, "In a year, it's all forgotten." He couldn't have been more wrong. The damage was crippling and the reputational damage lasted an entire generation. In fact, Austrian wine didn't catch up to the same level of exports that it had pre-1985 until 2001. This scandal therefore set the entire industry back 26 years. Although the scandal was a terrible thing to happen to the country of Austria and the livelihood of many honest people in the Austrian wine industry, it was probably the best thing to ever happen to Austrian wine itself. Right now the Austrian wine industry is doing the best it's ever done and making some of the best white wines in the world.

In particular, a personal favourite of mine that we sell at Weavers is the Domane Baumgartner which is packed full of fresh apple flavours, though the Villa Strass is also equally delicious. In addition to white wine we also sell some really fascinating (and delicious) dessert wine. For example, we’ve just got in some Austrian Eiswein. This is only produced in certain years when there is the perfect combination of low temperatures and high grape ripeness. The grapes must be harvested between -10°C and -15°C so that the water inside them freezes, leaving only pure grape juice behind. The grapes are then pressed in conditions between -6°C and -8°C degrees.

The fact that the harvest has to wait till after the grapes are ripe, means that the grapes may hang on the vine for several months following the normal harvest. If a freeze does not come quickly enough, the grapes may rot and the crop will be lost. If the freeze is too severe, no juice can be extracted. Vineland Winery in Ontario once broke their pneumatic press in the 1990s while pressing the frozen grapes because they were too hard (the temperature was close to −20 °C). The longer the harvest is delayed, the more fruit will be lost to wild animals and dropped fruit. Since the fruit must be pressed while it is still frozen, pickers often must work at night or very early in the morning, harvesting the grapes within a few hours, while cellar workers must work in unheated conditions for long periods.

The high sugar level of the grape juice leads to a slower-than-normal fermentation. It may take months to complete the fermentation (compared to days or weeks for regular wines) and special strains of yeasts have to be used. Because of the lower yield of grape musts and the difficulty of processing, ice wines are notorious challenging to produce on a large scale. However despite all these gruelling details the end product is simply delicious. Austrian Eiswien is rich sweet and sticky, perfect for any number of after dinner occasions.

I strongly recommend that you try out any Austrian wines you happen to find. While rarer than similar German wine they are uniquely consistent in their quality. Just look out for the lid with the trademark red background with a white cross.

Featured

Domäne Baumgartner Grüner Veltliner Trocken, Weinviertel 2022

Rich, zippy and spicy

What is MIX6?Add 6 or more bottles of selected wine to your basket to receive the wholesale price.

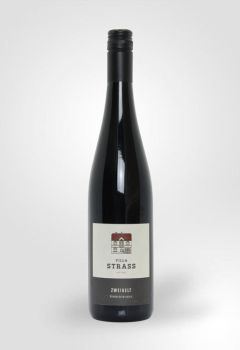

Villa Strass Zweigelt, Niederosterreich, 2021

Fresh and approachable

What is MIX6?Add 6 or more bottles of selected wine to your basket to receive the wholesale price.

Domaine Baumgartner Niefersterrich Eiswein, Austria, (Half Bottle), 2019

Rich and sweet

What is MIX6?Add 6 or more bottles of selected wine to your basket to receive the wholesale price.