-

- Origin

- Italy

- Trentino

A seductive rich red wine packed full with elegant red fruits and soft spices. Finished long and warming on the palate. Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Trentino

A seductive rich red wine packed full with elegant red fruits and soft spices. Finished long and warming on the palate. Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

- Southern

- Puglia

A soft and very approachable juicy red from Italy. Made from 100% Sangiovese which makes for a delightfully easy drinking red wine. Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Southern

- Puglia

A soft and very approachable juicy red from Italy. Made from 100% Sangiovese which makes for a delightfully easy drinking red wine. Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Ruby red colour. Intense aromas of cherry & blackberry combine with notes of liquorice & tobacco. The structure is large & enveloping with a long & pl... Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Ruby red colour. Intense aromas of cherry & blackberry combine with notes of liquorice & tobacco. The structure is large & enveloping with a long & pl... Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Ruby red colour. Intense aromas of raspberry and blackberry combine with notes of liquorice & coffee. The structure is large and enveloping with a lon... Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Ruby red colour. Intense aromas of raspberry and blackberry combine with notes of liquorice & coffee. The structure is large and enveloping with a lon... Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

Elegant, well structured and finely balanced this is an extemely complex wine with a wonderful soft mouthfeel and a long finish. Read More- Origin

- Italy

Elegant, well structured and finely balanced this is an extemely complex wine with a wonderful soft mouthfeel and a long finish. Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

An intense and elegant Brunello. A balanced and fruit driven nose with aromas of plums, cherries with a touch or orange and hint of spice. The palate ... Read More- Origin

- Italy

An intense and elegant Brunello. A balanced and fruit driven nose with aromas of plums, cherries with a touch or orange and hint of spice. The palate ... Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

- Central

- Tuscany

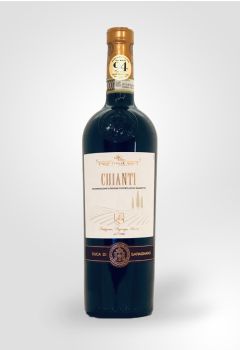

Light and very approachable, this is an easy-drinker suitable for most occasions. Lovely fresh cherry fruit content is presented with medium to light ... Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Central

- Tuscany

Light and very approachable, this is an easy-drinker suitable for most occasions. Lovely fresh cherry fruit content is presented with medium to light ... Read More -

- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Light in character with low tannin and plenty of cherry fruit flavour. A very approachable wine that is delicious on a warm day, a real thirst-quenchi... Read More- Origin

- Italy

- Tuscany

Light in character with low tannin and plenty of cherry fruit flavour. A very approachable wine that is delicious on a warm day, a real thirst-quenchi... Read More

It is difficult to generalise, for there are 14 sub-varieties of vastly differing type and quality (indeed, the four main ones produce wines with such varying characteristics that one could be forgiven for not deducing their shared ancestry).

Sangiovese is the lifeblood in most central Italian reds; it is the only variety permitted in Brunello di Montalcino (Brunello, meaning 'little brown', is one of the four main offspring varieties, having first been planted by the Biondi-Santi family at the end of the 19th century - most Sangiovese in Tuscany is now either Brunello or a sub-variety that is very similar) and the principal component in the blends for Chianti, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Morellino di Scansano and most modern supertuscans (in which Sangiovese is blended with a non-Italian varietal such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot) such as Tignanello (in this case, Sangiovese and Cabernet Sauvignon).

Key Regions

ITALY: Tuscany (here used for Chianti, Brunello di Montalcino and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano); Umbria (here, to the south of its Tuscan heartland, the variety is crucial for making quality wines) and Romagna - most notably Bologna (here, to the north, it is prized more for its quantity)

FRANCE: Corsica - known as Niellucciu, it is grown on the slopes of Sciacarellu and has overtaken the local variety Sciacarello/Sciaccarello (pronounced 'shackarello') to become predominant in the majority of the island's wines; in particular, it is to be found in the appellation of Patrimonio.

NORTH AMERICA: California (mostly in the Napa Valley) - it was introduced here by Italian immigrants in the late 1800s, but has only garnered popular interest recently with the popularity of the supertuscans - and Washington State.

SOUTH AMERICA: Argentina (mostly in the Mendoza province).

AUSTRALIA: (introduced here in the late 1960s, it is becoming more important as Australian winemakers look for a greater diversity of varieties to counter the tendency to rely too much on certain popular varieties like Shiraz and Chardonnay)

Climate Suitability

While Sangiovese vines are usually fairly sturdy and disease-resistant, the small bluish-black berries are quite thin-skinned and so have a vulnerability to rot. This is especially the case in damp and cool years, which, unfortunately, occur more often than not in Tuscany during October (it is a region which can appear extremely bleak in winter).

The late-ripening nature of the variety can be either a blessing or a curse, for in a dry, hot climate - in which Sangiovese thrives - it creates rich and long-lived wines, whereas cool years mean harsh tannins and high levels of acidity. The variety performs well in various types of soil but perhaps finds its most elegant and memorable expression when grown in those containing limestone, which seem to allow the wonderful aromas that are inherent in the grape to be fully revealed.

Only the best vineyards produce consistently good wines with this variety. Over the years Sangiovese has in some cases, alas, suffered from overproduction and poor vinification. The former has led to light-coloured, poor-quality wines of high acidity. This was especially so in Romagna in the late 1960s and early 1970s whan inferior offspring varities that gave high yields were widely planted. Greater care has been taken with recent plantings.

Colour and Flavours

The colour of the wines vary from deep ruby-red to garnet-red, depending on the method of vinification used. Over-production usually results in a lighter wine, whereas those with yields kept low develop deeper colours (the latter is especially true of the better wines).

Styles can differ considerably, from fairly unremarkable wines made to be drunk young - some basic Chiantis, for example - through to astoundingly complex wines such as Brunello, which can be matured for a couple of decades (some even say a century).

In the best expression of this variety, one might detect rustic aromas of black cherry, Morello cherry, blackberry, leather, herbs and even, depending on the terroir, a smokiness; concentrated flavours of vanilla, bitter cherry, blackberry, herbs and, with age, plum and truffle accompany lovely silky tannins.

Synonyms

Brunello, Brunello di Montalcino (in the southern Tuscan zone of Montalcino); Calabrese; Cardisco; Cordisio; Dolcetto Precoce; Ingannacane; Lambrusco Mendoza; Maglioppa; Montepulciano; Morellino; Morellone; Negretta; Nerino; Niella; Nielluccia, Nielluccio (in Corsica); Pigniuolo Rosso; Pignolo; Plant Romain; Primaticcio; Prugnolo, Prugnolo di Montepulciano, Prugnolo Gentile, Prugnolo Gentile di Montepulciano (in the Montepulciano region); Riminese; San Zoveto; Sancivetro; Sangineto; Sangiovese dal Cannello Lungo; Sangiovese di Lamole; Sangiovese Dolce; Sangiovese Gentile; Sangiovese Grosso; Sangiovese Nostrano; Sangiovese Toscano; Sangioveto dell'Elba; Sangioveto Dolce; Sangioveto Grosso; Sangioveto Montanino; Sanvincetro; Sanzoveto; Tignolo; Tipsa; Toustain; Uva Abruzzi; Uva Tosca; Uvetta; San Gioveto; Uva Brunella; Uva Canina