-

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Rich and slightly creamy, this Crémant from the highly acclaimed co-operative, Cave de Lugny, shows notes of citrus and apple with a fresh and crisp ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Rich and slightly creamy, this Crémant from the highly acclaimed co-operative, Cave de Lugny, shows notes of citrus and apple with a fresh and crisp ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lighter and more mineral style of Grand Cru Chablis. This is due to the vineyard facing south western which makes for a cooler mesoclimate than the ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lighter and more mineral style of Grand Cru Chablis. This is due to the vineyard facing south western which makes for a cooler mesoclimate than the ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

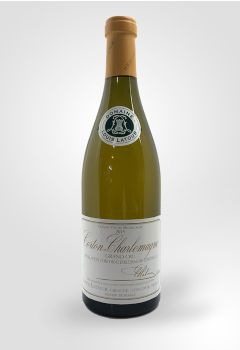

A beautifully balanced white Burgundy with an expressive bouquet of honey, brioche and vanilla on the nose and palate. The long and silky finish bring... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

A beautifully balanced white Burgundy with an expressive bouquet of honey, brioche and vanilla on the nose and palate. The long and silky finish bring... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

An absolutely stunning white Burgundy from the renowned Chateau de Blagny. Expect expressive aromas of honey, peach, and toasted almonds. Extremely el... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

An absolutely stunning white Burgundy from the renowned Chateau de Blagny. Expect expressive aromas of honey, peach, and toasted almonds. Extremely el... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

This soft, elegant wine has aromas of flowers, citrus fruits and honey, with a lovely warming toastiness which combines with more subtle ideas of almo... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

This soft, elegant wine has aromas of flowers, citrus fruits and honey, with a lovely warming toastiness which combines with more subtle ideas of almo... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lighter and more mineral style of Grand Cru Chablis. This is due to the vineyard facing south western which makes for a cooler mesoclimate than the ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lighter and more mineral style of Grand Cru Chablis. This is due to the vineyard facing south western which makes for a cooler mesoclimate than the ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lively, expressive white with subtle notes of ripe mango, passion fruit, tropical flowers, and vanilla. On the palate, the wine is textured and well... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A lively, expressive white with subtle notes of ripe mango, passion fruit, tropical flowers, and vanilla. On the palate, the wine is textured and well... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Elegant and refined, this white Burgundy displays restrained aromas of vanilla and fresh fruit, with subtle cedar notes from its time in oak. The plea... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Elegant and refined, this white Burgundy displays restrained aromas of vanilla and fresh fruit, with subtle cedar notes from its time in oak. The plea... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Considerable care has gone into this white Burgundy’s oak maturation resulting in a beautifully rounded and elegantly rich full-bodied wine. You ca... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Considerable care has gone into this white Burgundy’s oak maturation resulting in a beautifully rounded and elegantly rich full-bodied wine. You ca... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

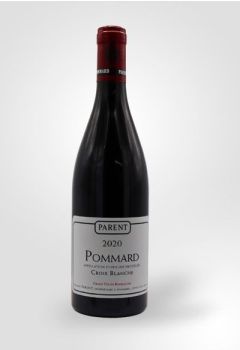

This characterful red displays rich, dark and spicy aromas adorned with lighter hints of floral and wood notes. Rich in the mouth, yet perfectly balan... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

This characterful red displays rich, dark and spicy aromas adorned with lighter hints of floral and wood notes. Rich in the mouth, yet perfectly balan... Read More -

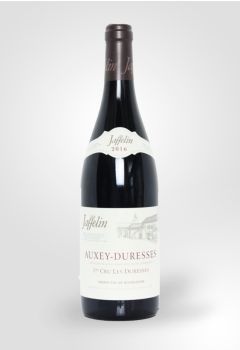

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

An elegant and gorgeously fruity wine, perfumed and balanced with incredibly supple tannins behind. On the palate there are sweet red fruits, spiced b... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

An elegant and gorgeously fruity wine, perfumed and balanced with incredibly supple tannins behind. On the palate there are sweet red fruits, spiced b... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

A stunning, one of the fuller-bodied red Burgundies showcasing powerful notes of wild cherries and blackberries, expressing a beautiful balance betwee... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

A stunning, one of the fuller-bodied red Burgundies showcasing powerful notes of wild cherries and blackberries, expressing a beautiful balance betwee... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

A divine elegant structured Burgundy made by Alain Chavy on his small 17 acres of vineyards in the premium wine region of Puligny Montrachet. Describe... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

A divine elegant structured Burgundy made by Alain Chavy on his small 17 acres of vineyards in the premium wine region of Puligny Montrachet. Describe... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

With a vibrant aromatic nose of damson and plums this fuller floured Pinot Noir moves to a deep concentrated palate with a fresh and refined finish. Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

With a vibrant aromatic nose of damson and plums this fuller floured Pinot Noir moves to a deep concentrated palate with a fresh and refined finish. Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Pale-yellow in colour, this soft and delicate Macon has an expressive bouquet of citrus fruit and honeysuckle which is then complimented by notes of s... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Pale-yellow in colour, this soft and delicate Macon has an expressive bouquet of citrus fruit and honeysuckle which is then complimented by notes of s... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Golden yellow in colour with green tints; the nose shows fresh apple and pear, with nutty aromas, and the palate is rich and round with well-balanced ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Golden yellow in colour with green tints; the nose shows fresh apple and pear, with nutty aromas, and the palate is rich and round with well-balanced ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Brilliant ruby red with vibrant aromas of cherries and red fruits. These characters follow through on t the palate with a touch of spice. A beautifull... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Brilliant ruby red with vibrant aromas of cherries and red fruits. These characters follow through on t the palate with a touch of spice. A beautifull... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Entices with vibrant notes of ripe citrus and toasted almonds. Delicate minerality intertwines seamlessly, while a creamy texture elevates the experie... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Entices with vibrant notes of ripe citrus and toasted almonds. Delicate minerality intertwines seamlessly, while a creamy texture elevates the experie... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

This is a Bourgogne Rouge which is supple, fresh & offers great elegance. It is a beautifully vibrant wine, brimming with ripe, red berry fruit, b... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

This is a Bourgogne Rouge which is supple, fresh & offers great elegance. It is a beautifully vibrant wine, brimming with ripe, red berry fruit, b... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Round with a pungent bouquet of grilled almonds and vanilla. Nice fullness in the mouth with integrated oak and a long, mineral finish. Despite being ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

Round with a pungent bouquet of grilled almonds and vanilla. Nice fullness in the mouth with integrated oak and a long, mineral finish. Despite being ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A modern style Chablis jam packed with fresh, green apples and hints of citrus. A firm, refreshing mineral backbone runs through the palate and on to ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

A modern style Chablis jam packed with fresh, green apples and hints of citrus. A firm, refreshing mineral backbone runs through the palate and on to ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

Jean-Marc Brocard is one of the leading Chablis producers. This is a classic wine displaying the character of a true Chablis. Hints of lemon and white... Read More- Origin

- France

- Burgundy

- Chablis

Jean-Marc Brocard is one of the leading Chablis producers. This is a classic wine displaying the character of a true Chablis. Hints of lemon and white... Read More

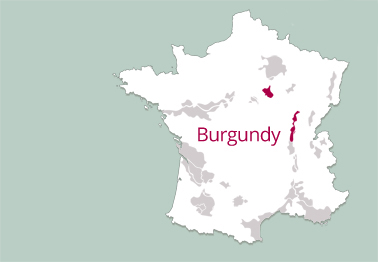

French inheritance laws ensure that small producers still thrive, alongside the larger négociants that buy in their grapes, and where some almost always excel there are those who are rather more hard to pin down. The name of the producer, which appears in smaller print than the appellation on the label and is traditionally regarded as of lesser importance, is often the real key to quality in Burgundy. When they succeed, their wines are sublime.

Styles of Wine

Chablis is always white and has two personalities, determined by whether oak has been used in its ageing. The district is split between those who insist on it and those who regard it as the work of the devil. The only way to tell is by asking. For other whites, as a rule, the Côte d'Or will use oak and elsewhere will not but the label will never divulge. Yet irrespective of wood the Chardonnay grape is extremely adaptable and different districts have their very own characteristics.

In a red burgundy the grape will shine through, being subtle, sensuous and strangely sweet when produced to its potential. Beaujolais wines are red, fruity and light.

Key Vines

Burgundy is regarded as the home of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir and these two grapes make most of the wines of the region. The rest of the world strives to replicate the styles they produce here.

Gamay is the grape for Beaujolais and the minor white grape of Aligoté also appears. Small plantings of Pinot Blanc are found mainly in the south.

Climate and Terroir

The importance of terroir reaches mystical heights throughout the vineyards of Burgundy. This delicate combination of soil, aspect, topography and something indefinable accounts for the complexities of the appellation system and the variabilty of the wines. It is one reason why the great and the decent have each other for neighbours.

Burgundy, climatically, is marginal land for the growing of grapes. Frost, heavy rainfall, hail and not enough heat will regularly have an impact. Chardonnay is a hardy little grape that will take all of this in its stride, but Pinot Noir is altogether more delicate and vintages vary enormously in quality. When things come together, however, the results are amazing.

The Role of the Winemaker

This, obviously, is always imperative for every winery in the world, but Burgundy plays by its own set of rules. French inheritance laws established under Napoleon require land bequeathed to be equally split between all of the children. In Burgundy, where the land is so fruitful and prestigious, this has been applied with rigour. Individuals, as a consequence, may own only a couple of rows of vines within a vineyard. This has led to two very different styles of winemaker.

The first of these is the individual producer, the person who owns the vines, and whose wine will often be labelled Domaine on the bottle. In the right hands these are superb, and often exclusive, but some individuals have neither the resources nor the expertise to maximise their grapes. Secondly comes the négociant, a larger-scale operator who buys in grapes to blend and then bottles them under his own name. Some are excellent, others less so, and as with individuals the name of the producer is of utmost importance.

Influence on the World

The Chardonnay grape has spread from its home in Burgundy and conquered the world. It is hardy, tolerant, adaptable and eager to please and so its widespread success is no great surprise. Many, however, would say that it is still at its best when it comes out of Burgundy.

The worldwide adoption of Pinot Noir is a different story altogether. It is a trial to grow and elusive to master, but everyone seems to be having a go. The reason for this is quite simple: there can be no greater accolade than to create a Pinot Noir to rival red Burgundy.