-

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Saint-Emilion

A glorious, elegant red displaying sweet red cherry and raspberry that give the wine brightness and lift. The aromatics are intriguing, complex and in... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Saint-Emilion

A glorious, elegant red displaying sweet red cherry and raspberry that give the wine brightness and lift. The aromatics are intriguing, complex and in... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

A soft wine with attractive berry fruits, smoky acidity and sweet juicy flavours. The tannins are well integrated with acidity pushing through. The fi... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

A soft wine with attractive berry fruits, smoky acidity and sweet juicy flavours. The tannins are well integrated with acidity pushing through. The fi... Read More -

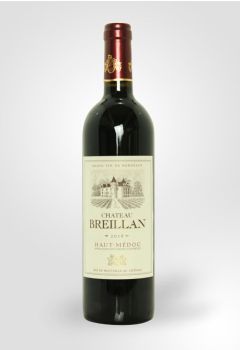

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Haut-Medoc

A beautiful and intense claret with red fruits, vanilla and spice on the nose which follow through to the full bodied palate that has a wonderful rich... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Haut-Medoc

A beautiful and intense claret with red fruits, vanilla and spice on the nose which follow through to the full bodied palate that has a wonderful rich... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

Rich, muscular and complex with layered aromas of elegant damson, eucalyptus and brooding black fruits. Silky Pomerol tannins lead to a long and sumpt... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

Rich, muscular and complex with layered aromas of elegant damson, eucalyptus and brooding black fruits. Silky Pomerol tannins lead to a long and sumpt... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

A rich Claret that has an aromatic nose of fresh fruit and black berries with a hint of toast. It is structed with an elegance and balance that reveal... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

A rich Claret that has an aromatic nose of fresh fruit and black berries with a hint of toast. It is structed with an elegance and balance that reveal... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Graves

A beautiful deep garnet with an evocative nose exhibiting red berried fruit and dark chocolate. It is soft and round which gives a mouth filling palat... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Graves

A beautiful deep garnet with an evocative nose exhibiting red berried fruit and dark chocolate. It is soft and round which gives a mouth filling palat... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Medoc

A tapestry of rich, ripe blackberries and cassis, interwoven with hints of cedar and tobacco. Firm tannins provide structure, while a velvety texture ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Medoc

A tapestry of rich, ripe blackberries and cassis, interwoven with hints of cedar and tobacco. Firm tannins provide structure, while a velvety texture ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Pauillac

Derived from premier vineyards in Pauillac, three out of the initial five classified growths of 1855 hail from this renowned appellation, nestled on t... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Pauillac

Derived from premier vineyards in Pauillac, three out of the initial five classified growths of 1855 hail from this renowned appellation, nestled on t... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

A stunning, full bodied expansive beauty of a wine, it is quintessentially Margaux with a Pomerol-like richness. It is silky and gorgeous with unbelie... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

A stunning, full bodied expansive beauty of a wine, it is quintessentially Margaux with a Pomerol-like richness. It is silky and gorgeous with unbelie... Read More -

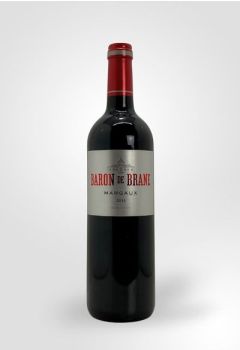

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

Deliciously fresh and fragrant, this is a very powerful wine with remarkable structure, beautiful tannins and lovely texture. Intense, Christmas cake ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

Deliciously fresh and fragrant, this is a very powerful wine with remarkable structure, beautiful tannins and lovely texture. Intense, Christmas cake ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

A well-structured wine with firm tannins and a distinctive black fruit character. Drinking well now but will develop favourably over the next 5-10 yea... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

A well-structured wine with firm tannins and a distinctive black fruit character. Drinking well now but will develop favourably over the next 5-10 yea... Read More -

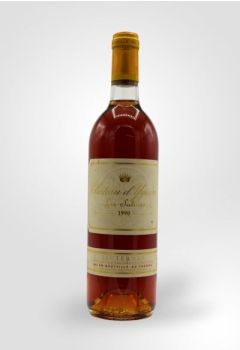

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

A splendid sweet wine from this exceptional world class Estate. Honey, peaches and apricots abound in layers. Beautifully balanced and captivating. Dr... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

A splendid sweet wine from this exceptional world class Estate. Honey, peaches and apricots abound in layers. Beautifully balanced and captivating. Dr... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

A fresh style of Claret which is lighter than many St Juliens. Rich fruit and soft spice on both the nose and palate lead to a good finish with gentle... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

A fresh style of Claret which is lighter than many St Juliens. Rich fruit and soft spice on both the nose and palate lead to a good finish with gentle... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

An expressive nose of dense, ripe blackberries, soft spice and leathery notes. The palate is firm with sweet tannins and a fabulously long finish. Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

An expressive nose of dense, ripe blackberries, soft spice and leathery notes. The palate is firm with sweet tannins and a fabulously long finish. Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

Ripe and concentrated black fruit on the nose leads on to a savoury palate. This is an impeccably well structured wine with a fabulously long finish w... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- St-Julien

Ripe and concentrated black fruit on the nose leads on to a savoury palate. This is an impeccably well structured wine with a fabulously long finish w... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

Surperbly aromatic with notes of smoke leather and spicy red berry fruits. Medium-bodied on the mouth with great depth of flavour showing cassis and... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Margaux

Surperbly aromatic with notes of smoke leather and spicy red berry fruits. Medium-bodied on the mouth with great depth of flavour showing cassis and... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Saint-Emilion

A suductively rich aroma of plums, vanilla and chocolate. Spice, complexity with almost a stewed cherry character. Long and very firm on the finis... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Saint-Emilion

A suductively rich aroma of plums, vanilla and chocolate. Spice, complexity with almost a stewed cherry character. Long and very firm on the finis... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

Sourced from fruit near the town of Le Réole, this lovely example of an everyday Claret has great depth of colour good juicy cassis fruits. Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

Sourced from fruit near the town of Le Réole, this lovely example of an everyday Claret has great depth of colour good juicy cassis fruits. Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

The nose is expressive on notes of fruit and lots of spice; it reveals ripeness and is very fresh. On the palate, this wine is charming, with surprisi... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

The nose is expressive on notes of fruit and lots of spice; it reveals ripeness and is very fresh. On the palate, this wine is charming, with surprisi... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Pauillac

An elegant red from Pauillac which displays rich fruit flavours which are lifted by more floral notes upon aeration. The palate is medium-bodied with ... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Left Bank

- Pauillac

An elegant red from Pauillac which displays rich fruit flavours which are lifted by more floral notes upon aeration. The palate is medium-bodied with ... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeux

- Left Bank

An excellent modern Sauternes from the first growth Chateau Guiraud. Expect pronounced aromas of apricots, dates and almond cream intertwined with une... Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeux

- Left Bank

An excellent modern Sauternes from the first growth Chateau Guiraud. Expect pronounced aromas of apricots, dates and almond cream intertwined with une... Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

Sourced from fruit near the town of Le Réole, this lovely example of an everyday claret has great depth of colour and nice juicy cassis fruits. Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

Sourced from fruit near the town of Le Réole, this lovely example of an everyday claret has great depth of colour and nice juicy cassis fruits. Read More -

- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

A stunning Pomerol full of expressive notes of black and red currant, intertwined with notes of leather and chocolate. Read More- Origin

- France

- Bordeaux

- Right Bank

- Pomerol

A stunning Pomerol full of expressive notes of black and red currant, intertwined with notes of leather and chocolate. Read More

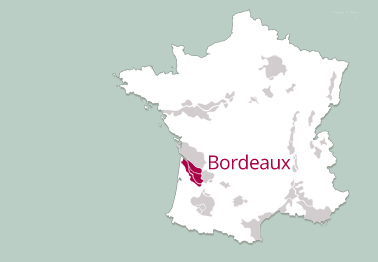

Geography

Bordeaux crafts the world's greatest wines from the planet's most famous estates, but with over 100,000 hectares under vine (more than many a winemaking nation) it also produces a vast amount of everyday wine at affordable prices. It is divided into the Left Bank, the Right Bank and the Entre-Deux-Mers and within these are such famous areas as the Médoc, St-Julien, Graves, St-Émilion and Sauternes. It is famous for its red wines, but its sweet whites are excellent and its dry whites of note. Bordeaux, quite simply, is a place like no other.

History

It is long, and of course complex, and the British play a significant part. When the future Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152 he knew he had made a good deal, but even he could not have foreseen the remarkable long-term benefits of the union. For she came with Bordeaux as a dowry and a trade was established that has very rarely lapsed. Wine flowed in to Britain, aided by tax breaks, and the region was established as a winemaking giant.

It was not until the 18th century, however, that the fine wines we know of today came into existence. Affluence brought this about: in the British aristocracy, the French winemakers and the several nationalities of merchant who set up in Bordeaux. Claret, as Bordeaux was known in England, became a status symbol and the demand for ever more quality was created and fulfilled. Much the same situation exists to this day.

Styles of Wine

Bordeaux, both red and white, is a blend and therefore remarkably varied. Most of the wine, and almost all of the great, is red. As a rule it is softer and subtler than New World equivalents and has the structure to complement rather than clash with a wide range of foods. Yet in such a diverse region this is a gross generalisation. Pauillac and St-Julien, for example, may be adjoining but at the top of their game they are incredibly different and individual appellations have their very own character. The sweet whites of Sauternes and Barsac are amongst the finest dessert wines to be found in the world. Though the dry whites are comparatively undistinguished, they are eminently drinkable and occasionally capable of excellent ageing.

Key Vines

The Bordeaux Classification lays down the law. Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc and, to a lesser extent, Malbec and Petit Verdot are blended in the creation of reds and Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle (though predominantly the first two) are combined for the sweet and dry whites.

Climate and Terroir

To put it simply, Bordeaux has a mild and stable climate of no extremes. Elsewhere in the world this might result, each and every year, in dull generic wines. Bordeaux does not work like that. The topsoil is basically poor, which is generally advantageous to vines, and beneath it is a mosaic of very different bedrock. This allows for great variation, though as yet science has been unable to pinpoint why even neighbouring properties can be so contrasting in quality and character. In a nutshell, terroir is all-important, and terroir is inexplicable, and that is just the way the French like it to be. The mystery is all part of the appeal.